Chapter 8.

Kingpins of Christianity

This chapter introduces five men who were fundamental in defining Christianity as we know it today: St. Paul the Apostle, Constantine the Great, St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, and Martin Luther. These men were major figures in Christian history. Their influence is indelibly stamped upon Christian theology.

In this chapter, I discuss the beliefs and impact of each of these men. The sections are as follows:

Note:

BCE stands for Before the Common Era, that is, before the birth of Jesus of Nazareth, and CE stands for Common Era, which began with the birth of Jesus. The biblical scripture is from the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV).

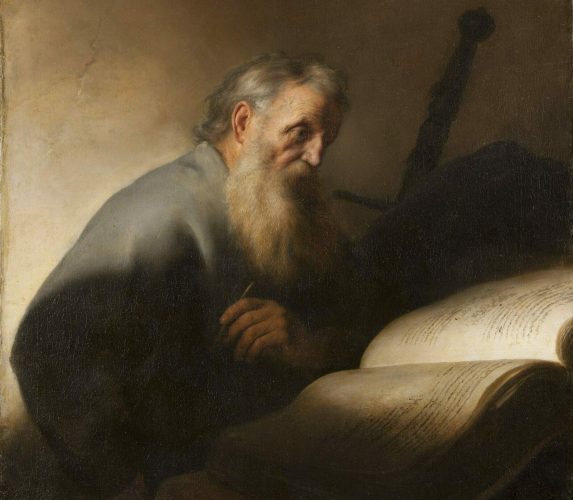

St. Paul the Apostle (Born 5 BCE to 5 CE; Died Age 64 to 67)

Paul is commonly known as Saint Paul, as well by his Hebrew name, Saul of Tarsus. The book of Acts indicates that Paul was a Roman citizen by birth. He was born into a Jewish family in the city of Tarsus (located in modern day Turkey). Paul spoke and wrote Greek fluently, and he also spoke Hebrew. He was a devout and highly educated Jew, who never married. He was a tent maker by trade.

Several years after Jesus was crucified, Saul of Tarsus began actively persecuting Christians. He authorized and was present at the death by stoning of St. Stephen, who was accused of blasphemy. Sometime after this, Saul set out to visit Damascus to persecute Christians. On the road to Damascus, he reported experiencing a life-altering vision of Jesus. Reportedly, Paul was blinded for three days before recovering his eyesight.

Though he never knew Jesus in person, Paul’s vision and recovery from blindness caused him to convert to Christianity and to embark on a life devoted to proselytizing. Unlike earlier Christian leaders, Paul preached to gentiles, establishing Christian communities in several cities in the eastern Mediterranean. He wrote letters, known as epistles, to these communities to help their members understand his teachings. Some of his epistles survived to become books in the Christian Bible.

In the Apostolic Age, Paul holds a dominant position. Of the 27 books of the New Testament, 14 have been attributed to him. Of these, seven books are widely considered to be authentic, while the authenticity of the remaining seven receives varying degrees of support. The core group of seven epistles that are nearly universally considered to be authentic include: 1 Thessalonians, Galatians, 1 Corinthians, 2 Corinthians, Philemon, Philippians, Romans | 1-15 | 16.

Paul’s Christian theology was born of Judaism and his visionary experience of Jesus. He taught that only the Jewish God was to be worshiped, and that Jesus was his Son, who had died for the sins of the world. Paul is credited as the one who came up with the meaning of Jesus’s death and resurrection. He also taught that the end of the world was imminent.

Paul proclaimed himself to have come directly from God and Christ. In Galatians 1:1-2, Paul wrote, “Paul an apostle – sent neither by human commission nor from human authorities, but through Jesus Christ and God the Father, who raised him from the dead – and all members of God’s family who are with me.”

![08. KOC-Conversion_of_St._Paul_DPLA_0a3c91557f2fac7d1a8950bfa01ac226 [SMALLER, w-o frame] Conversion of St. Paul](https://b2348605.smushcdn.com/2348605/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/08.-KOC-Conversion_of_St._Paul_DPLA_0a3c91557f2fac7d1a8950bfa01ac226-SMALLER-w-o-frame-e1713290929648-qmt1jxpxn41lvv9cjhu5jk4ph03l7jidbwekx005j4.png?lossy=1&strip=1&webp=1)

Yet he believed women to be inferior to men—not fully part of God’s family: “I want you to understand that Christ is the head of every man, and the husband is the head of his wife, and God is the head of Christ (1 Corinthians 11:3 (NRSV)).” He wanted women to be veiled in church, but not men: “For a man ought not to have his head veiled, since he is the image and reflection of God; but woman is the reflection of man. Indeed, man was not made from woman, but woman from man. Neither was man created for the sake of woman, but woman for the sake of man” (1 Corinthians, 11:7-9).

Paul was a deeply conflicted individual. He cared intensely for the struggling Christian communities he helped establish, but he had difficulties getting along with them. In his letter to the Corinthians, 2 Corinthians 12:20, Paul wrote, “For I fear that when I come, I may find you not as I wish, and that you may find me not as you wish; I fear that there may perhaps be quarreling, jealousy, anger, selfishness, slander, gossip, conceit, and disorder.” In his letter to the Galatians, Galatians 5:12, he wrote, “I wish those who unsettle you would castrate themselves.”

The following passage reflects Paul’s guilt and self-loathing. In Romans 7:14-20, Paul tells the Romans:

For we know that the law is spiritual, but I am of the flesh, sold unto slavery under sin. I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate. Now if I do what I do not want, I agree that the law is good. But in fact it is no longer I that do it, but sin that dwells within me, that is, in my flesh. I can will what is right but I cannot do it. For I do not do the good I want, but the evil that I do not want is what I do. Now if I do what I do not want, it is no longer I that do it, but sin that dwell within me.

Two books of debatable authenticity, Colossians and Ephesians, contain pro-slavery quotations. Regardless of who authored these two epistles, it is evident that Paul’s authority was used to justify slavery, whether it was his personal belief or not. Colossians 3:22 instructs, “Slaves, obey your earthly masters in everything, not only while being watched and in order to please them, but wholeheartedly, fearing the Lord.” Ephesians (6:5–6), instructs, “Slaves, obey your earthly masters with fear and trembling, in singleness of heart, as you obey Christ; not only while being watched, and in order to please them, but as slaves of Christ, doing the will of God from the heart.”

Tragically, for over eighteen hundred years, slavery persisted in the Christian West, being bolstered by the justifications of slavery in Colossians and Ephesians, writings attributed, rightly or wrongly, to Paul. Like other biblical texts these books have often been accepted as the inerrant word of God.

Eventually, Paul was imprisoned for his teachings by the Romans in Caesarea. Later, he was sent as a captive to Rome, where, after two years, he was beheaded.

Constantine the Great is also known as Constantine I and, historically, as the “First Christian Emperor”, 306 to 337 CE. After defeating his rival, Roman emperor Maxentius, just outside Rome in 312 CE, Constantine became the Western emperor of the Roman Empire. Constantine, who had adopted Christianity, attributed this victory over Maxentius to the help of “the supreme deity.” There is much disagreement among historians about the nature of Constantine’s “conversion.” Some believe that Constantine was guided by the Christian God in this victory. Others have considered his “conversion” as a purely political maneuver.

Modern historians have found little evidence that Constantine understood the Christian religion at the time of his “conversion,” nor for some time afterwards. It was traditional in Roman society to be brought up with an allegiance to several cults at the same time. Constantine’s patronage of the Roman deities Apollo, Hercules, and Sol Invictus reflects this custom. There is also little evidence that Constantine attended Christian church services until shortly before his death. Only then did he finally allow himself to be baptized.

Attempts by the Romans to eradicate Christianity through persecution had failed. Whether out of gratitude to the Christian God for his victory over Maxentius or in an effort to unite his chaotic empire, Constantine soon ended persecution of Christians. In 313 CE, the year after becoming the Western emperor, Constantine, together with the head of the Eastern Empire, Licinius, issued a proclamation in Milan, known as the Edict of Milan. This proclamation provided that Christians were to be treated benevolently.

Constantine ordered that anyone taking property from any church of the catholic Christian communities during the previous decades return it to the same church. He allocated money to repair damaged churches and ordered new ones to be built. Constantine provided gifts of money, and tax breaks to the bishops. However, he began taking an adversarial approach to those who were considered enemies by catholic Christianity. He penalized Christians whose beliefs were not in alignment with catholic Christians.

Timothy Barnes, a foremost historian regarding the life of Constantine, wrote in his book, Constantine and Eusebius, “Constantine translated Christian prejudice against Jews into legal liabilities.” He prohibited Jews from entering Jerusalem except for the one day a year when they were supposed to morn from having lost it.” They were also forbidden to accept any converts to Judaism. According to Barnes, Constantine “prescribed that any Jew who attempted forcibly to prevent conversion from Judaism to Christianity should be burned alive.”

Constantine is renowned as a brilliant military leader. His defeat of his co-emperor, Licinius, in 324 CE, led to his becoming the sole Roman Emperor (of both the Western and Eastern empires) in 325 CE. Among his many accomplishments as emperor was the construction of an imperial residence in the city of Byzantium. He renamed the city Constantinople, after himself, and it became the capital of the Roman Empire for a thousand years. The city is now Istanbul, Turkey. He also built the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in the old city of Jerusalem and Saint Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City within the city of Rome.

In the early 4th century CE, Christianity was beset by power struggles and doctrinal disputes. The year that Constantine became the sole Roman emperor, a major doctrinal controversy erupted among Christian bishops, threatening Constantine’s dream of political stability. To address this controversy, Constantine invited all of the approximately 1,800 Catholic bishops from throughout his empire to attend a council to be held in Nicea, in present day Turkey. About 300 bishops showed up, along with their retinues. Constantine funded their travel and presided over the meeting. In speaking to the bishops, he said, “You do nothing but that which encourages discord and hatred, and, to speak frankly, which leads to the destruction of the human race.” (The Closing of the Western Mind by Charles Freeman)

The main doctrinal principle that the Council of Nicea agreed upon was that Jesus Christ, the Son of God, was not created, but has always existed, and is equal to God the Father. The council codified its agreements in a document known as the Nicene Creed. Several bishops refused to sign the document and were excommunicated and exiled by Constantine in a display of his imperial powers. Unfortunately, Constantine had failed to understand the severity of the division among the bishops. His hope of having the church as a united body brought into the structure of the empire by toleration, patronage, and tax exemptions soon proved to be an illusion.

Constantine had a very dark side. His personal brutality was shown when in 326 CE, he ordered the execution of Crispus, his son by his first wife. Shortly thereafter, according to the Latin Epitome de Caesaribus and the Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius (as epitomized by Photius), Constantine had his current wife, Empress Fausta, executed by being thrown into boiling water. Around this time, Constantine also had his brother-in-law, Licinius, and his nephew, Licinius II, executed.

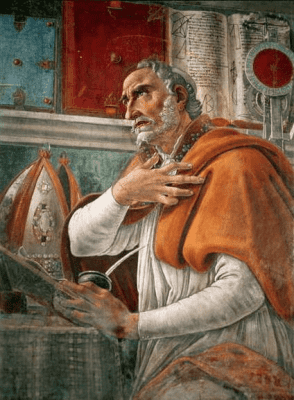

St. Augustine of Hippo (354–430)

Saint Augustine, the Bishop of Hippo in Roman North Africa, grew up as an only child in a small town in North Africa. Augustine’s mother, Monica, was a devout Christian, though his father was a pagan. His parents scrimped and saved so that, at the age of seventeen, he could attend the School of Carthage.

Augustine was afflicted with mental anguish and struggled with trying to understand the source of evil and suffering in the world. In his youth, he was drawn to the major gnostic religion at that time. This held his interest for nine years, but then he became dissatisfied with its beliefs and turned to Neoplatism. He went to Rome and Milan where he pursued academics, but he continued to struggle with theosophical and philosophical issues.

Throughout his youth, Augustine actively engaged in sexual relationships, but he eventually settled down and lived with a girlfriend for about fifteen years. She bore him a son, Adeodatus.

Augustine’s relationship with his mother was oftentimes emotionally conflicted. Monica was not happy with her son’s domestic arrangement, and at her urging, Augustine broke off with his girlfriend in 385. Monica wanted her son to be in a respectable marriage. She chose for him a ten-year-old girl from a well–connected family. He was to wait to marry her until she reached twelve, the legal age of marriage. However, during the time he was waiting to marry his fiancée, he converted to Christianity and was baptized. After his conversion, Augustine gave up his plans to marry, choosing a life of celibacy instead. A few years later, he became a priest. Eventually, he became the Bishop of Hippo, a position he held until his death.

Augustine’s conversion is attributable to the writings of St. Paul, who became a major influence on Augustine. He was a prolific writer. Among his many important works are On Christian Doctrine, Confessions, and City of God. His theological and philosophical perspectives were often at odds with other prominent Christian theologians of his time. He believed in an afterlife of an eternity in heaven or hell (see the “Post New Testament” section of the History of Heaven and Hell chapter). He was primarily responsible for formulating the doctrine of Original Sin (see the Original Sin chapter). This doctrine was disputed by many of his contemporary theologians. Other disputed teachings of Augustine were the doctrines of grace and of predestination. He is also recognized for his contributions in developing Just War Theory, which provides guidance for determining whether a war is justified and how to fight a just war.

Augustine struggled with uncertainty and guilt, as is revealed in his Confessions. This book marks the first view into the interior mind in western literature. One cannot read the Confessions without becoming aware of Augustine’s struggles with his sexual feelings and preoccupation with his own sinfulness:

I became evil for no reason. I had no motive for my wickedness except wickedness itself. It was foul, and I loved it. I loved the self-destruction, I loved my fall, not the object for which I had fallen but my fall itself. My depraved soul leaped down from your firmament to ruin. I was seeking not to gain anything by shameful means, but shame for its own sake. (Confessions)

This apparent self-contempt as written in Confessions is reflected in Augustine’s seeming disgust of humanity as evidenced in his On Free Choice Of The Will: “God, the highest Ruler of the universe, justly decreed that we, who are descended from that first union, should be born into ignorance and difficulty, and be the subject to death, because they [Adam and Eve] sinned and were hurled headlong into the midst of error, difficulty and death.”

In the City of God, Augustine writes that as a result of Adam’s sin the entire human race is a “train of evil”. This book was his last and perhaps greatest work. It was completed just four years before he died. The prominence of this book can be seen a thousand years later, in the 15th century, with the advent of the printing press. It was second only to the Bible in the number of copies published.

St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274)

Thomas Aquinas is one of the most influential theologians of all time—especially for Roman Catholics. He is one of Europe’s most outstanding champions of rational thought, even though he gave in to orthodoxy. The Catholic Church honors him as a saint, and his works are used to instruct people studying for the priesthood. His hymns are used in the mass.

He was born near Naples, Italy to an aristocratic Catholic family. Aquinas was sent off to a Benedictine abbey at the age of five. He went to Naples for university studies and became enthralled with the works of Aristotle. He defied his family’s firm directive that he join the Benedictine order and, instead, joined the relatively new and less distinguished Dominican order.

He attended the great university center in Paris for seven years of intensive study and returned to Italy with a license to teach theology. It was during this time that he produced his first great work, Summa Contra Gentiles, a defense of Christianity against unbelievers.

Aquinas accepted the Catholic articles of faith, but he didn’t denigrate reason the way many of his fellow Christians had done. He challenged the pessimism of Augustine and his followers, and he presented reason as a gift from God. Unlike Augustine’s view of man as a wretched creature helplessly mired in sin, Aquinas was naturally optimistic that humanity will use its God-given reason to find personal and spiritual fulfillment.

Aquinas wholeheartedly embraced the philosophy of Aristotle, whose insistence on the importance of rational thought and the accumulation of empirical evidence was crucial. Aquinas may have valued Aristotle’s work on the nature of man even more. According to Aristotle, it is the natural instinct of man to develop into his final and most complete form, that of a flourishing human being capable of using rational thought at the highest level. It was this high level of optimism that Aquinas infused into Christianity. Aristotle argued that it was the natural impulse of human beings to desire “the good.” Aquinas takes this a step further: the combination of the impulse to “the good” along with the power of rational thought allows human beings to understand what is morally right.

Aquinas was one of Europe’s most outstanding torchbearers of rational thought, but he still had to suspend his writings on the subject of reason when it came to church doctrine. Clearly, he was influenced as much by church doctrine as by Aristotle, and much of his work reflected his loyalty to Christian doctrine. Nevertheless, during his lifetime, as well as after his death, there was controversy within the church about his work.

Aquinas’s greatest work is Summa Theologica, translated as “Sum of Theology.” It consists of 1.8 million words and was unfinished at his death. This is considered the second most renowned work by a Catholic theologian.

This book reflects the cultural perspective of his era. His attitude toward the female gender was extremely oppressive. Summa Theologica reflects this:

Every woman is birth-defective, an imperfect male begotten because her father happened to be ill, weakened, or in a state of sin at the time of her conception.

Aquinas believed that women should be ruled by men because men are more intelligent and rational. He took his cue from Augustine to explain why women should be subordinate for their own good, “For good order would have been wanting in the human family if some were not governed by others wiser than themselves. So, by such a kind of subjection woman is naturally subject to man, because in man the discretion of reason predominates.” (Summa Theologica)

The Dominican order to which Aquinas belonged was committed to converting heretics to Catholicism—any person holding an opinion at odds with the Catholic Church was considered a heretic. The Dominican order was founded in 1215, during the 20-year Albigensian Crusade. The Dominicans began as an order dedicated to the conversion of the Cathars (of southern France), known as Good Christians to Catholicism. Though the Cathars were Christians, their beliefs weren’t totally in alignment with Catholic doctrine. But many Cathars proved recalcitrant, and conversion efforts often failed. If heretics could not be converted by peaceful means, the accepted alternative was putting them to death. Thousands of recalcitrant Cathars were slaughtered (primarily by forces of the French crown) under the auspices of the Catholic Church.

In justification of such slaughter, Aquinas wrote:

With regard to heretics two points must be observed: one, on their own side; the other, on the side of the Church. On their own side there is the sin, whereby they deserve not only to be separated from the Church by excommunication, but also to be severed from the world by death. For it is a much graver matter to corrupt the faith that quickens the soul than to forge money, which supports temporal life. Wherefore if forgers of money and other evil-doers are forthwith condemned to death by the secular authority, much more reason is there for heretics, as soon as they are convicted of heresy, to be not only excommunicated but even put to death.

On the part of the Church, however, there is mercy, which looks to the conversion of the wanderer, wherefore she condemns not at once, but ‘after the first and second admonition’, as the Apostle directs: after that, if he is yet stubborn, the Church no longer hoping for his conversion, looks to the salvation of others, by excommunicating him and separating him from the Church, and furthermore delivers him to the secular tribunal to be exterminated thereby from the world by death. (11, “Article 3”. Summa Theologica, II–II)

The term “abominable fancy” refers to the long-standing Christian idea that the eternal punishment of the damned in hell would entertain the saved. This idea was favored by luminaries through most of church history including Augustine and Aquinas. Aquinas wrote, “In order that the happiness of the saints may be more delightful to them and that they may render more copious thanks to God for it, they are allowed to see perfectly the sufferings of the damned.” This demonstrates Aquinas’s lack of compassion.

Martin Luther (1483–1546)

Martin Luther was born in Germany in 1483. His father, Hans, was a lease-holder of copper mines and smelters. Luther graduated from the University of Erfurt with a master’s degree in 1505. In accordance with his father’s wishes he enrolled in law, but soon became disinterested and dropped out.

Shortly thereafter, he was hit by a bolt of lightning and knocked to the ground. Terrified, he cried out to Catholicism’s patroness of miners, “Saint Anne, save me! And I’ll become a monk.” Some weeks later, he entered an Augustinian monastery.

He proved to be a very dedicated monk. He was driven by his sense of his own sinfulness and God’s greatness. In the monastery he pushed his body to extreme measures of austerity. He sometimes slept without a blanket in freezing weather, flagellated himself, and fasted for three-day intervals. Luther lamented, “If I had kept on any longer, I should have killed myself with vigils, prayers, reading and other work.”

Luther found his passion in the study of scripture. He was assigned to the chair of biblical studies at the recently established Wittenberg University. While studying the bible, Luther pondered the meaning of a sentence in Paul’s Epistle to the Romans. “Night and day I pondered,” he later recalled, “until I saw the connection between the justice of God and the statement that ‘the just shall live by his faith.’ Then I grasped that the justice of God is that righteousness by which through grace and sheer mercy God justifies us through faith. Thereupon I felt myself to be reborn and to have gone through open doors into paradise.”

This insight led to his revolutionary doctrine of justification by faith alone. If justification comes through faith in Christ alone, the intercession of priests is unnecessary. Faith formed by the Word of God required no monks, no masses, and no prayers to the saints. This meant that the Roman Catholic Church as an intermediary between man and God became meaningless. Of the seven sacraments of the church, he rejected all but baptism and marriage.

Surprisingly, it wasn’t Luther’s new doctrinal perspective that led him to confrontation with his church. Luther objected to the church selling “indulgences,” which were a way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo for sins. The sale of indulgences, introduced by the church during the crusades, was a preferred source of papal income. Luther was incensed that Christians, many of them poor, were giving their money to the church to supposedly have their sins forgiven or to free the souls of their deceased loved ones from purgatory. In 1517, in order to start a theological debate, Luther drew up a list of Ninety-Five Theses outlining his objection to the sale of indulgences. This list was met with forceful rejection, and eventually, Luther was excommunicated by the pope. The start of the Protestant Reformation is usually dated to the Ninety-Five Theses.

In 1519, Luther wondered why Jews would ever consider converting to the Christian faith given the “cruelty and enmity we wreak on them – that in our behavior towards them we less resemble Christians than beasts.” In the 1523 essay, That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew, he reached out to Jews in an attempt to move them to convert to Christianity.

Luther married Katharina von Bora in 1525, a few years after he helped her and a group of nuns escape from a Catholic convent. Their marriage became a model for the Protestant clergy, in direct opposition to the Catholic policy of a celibate clergy. Katharina bore him six children. However, though they had a happy marriage, Luther’s view of women was sexist, which was typical for the times. He wrote, “if women get tired and die of bearing [children], there is no harm in that; let them die as long as they bear; they were made for that.” (Sex and Power in History by Amaury de Reincourt)

The devil played an important role in the life of Luther, who reported having physical encounters with the devil. Luther wrote, “We are all subject to the Devil, both in body and goods…” According to Luther, “The Devil liveth, yea, and reigneth throughout the whole world…” Early in the reformation, the devil was conceived of as an increasingly powerful entity, who not only lacked goodness, but also had a conscious will against God and his creation. Luther’s fixation on the devil likely played a role in this perspective.

Luther remained an active scholar and author. He published a German translation of the New Testament, which influenced the development of a standard version of the German language. This was followed by his German Mass, and a translation of the Old Testament, which he produced with collaborators.

Luther also had a deep appreciation for music, “Music is a fair and lovely gift of God,” and wrote music for church services. Today, it is hard to imagine that before Luther, there was no congregational singing in churches.

By the time he was fifty, Luther was suffering from poor health. His deteriorating physical condition may have contributed to his irritability in his later years. Apparently, he had given up any hope of converting the Jews since he wrote That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew. He had turned aggressively against them by 1543, when he wrote On the Jews and Their Lives. In this, he advocated destroying Jewish houses, setting fire to their synagogues, and even confiscating their prayer books and money.

During the outbreak of the Reformation, the Catholic Church had been hunting, capturing, torturing and burning witches. Luther saw fit to continue this practice, “I would have no compassion for these witches; I would burn them all” (Table Talk).

Not long before his death, in 1546, Luther yet again expressed his outrage and anger towards the pope. He wrote, “The pope is not and cannot be the head of the Christian church. Instead, he is head of the accursed church of all the worst scoundrels on earth, a vicar of the devil, an enemy of God, and adversary of Christ, a destroyer of Christ’s churches, a teacher of lies, blasphemies, and idolatries…” (Against the Papacy in Rome).

Near the end of his life, in 1546 at his last sermon in Wittenberg, Luther voiced his contempt for reason: “But since the devil’s bride, Reason, that pretty whore, comes in and thinks she’s wise, and what she says, what she thinks, is from the Holy Spirit, who can help us, then? Not judges, not doctors, no king or emperor, because [reason] is the Devil’s greatest whore.”

Martin Luther is considered the father of the Protestant Reformation, which transformed not only Christianity, but all of Western Civilization. Despite his failings, once he took a view of the bible that was different from the Catholic interpretation, our modern idea of freedom was born.