Chapter 11.

The Delusion of Satan

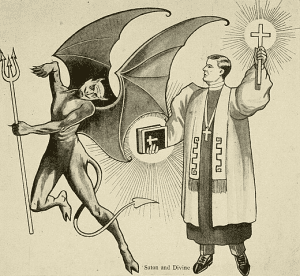

Satan is a problematic figure in Christian theology. He is best known as the personification of evil, an adversary of God and God’s people. In Christian theology Satan is also known as the devil and, sometimes, as Lucifer and Beelzebub. Satan was never physically described in the Bible, but he is often depicted as a naked red male creature with two large bat-like wings, two horns, a tail, and a pitchfork. He didn’t start out this way.

In this chapter, I discuss the origins of Satan and his role in Christianity. The sections are as follows:

Note: BCE stands for Before the Common Era, that is, before the birth of Jesus of Nazareth, and CE stands for Common Era, which began with the birth of Jesus. Biblical scripture is from the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV).

Hebrew Origin

A figure known as ha-satan (“the satan”) originally appeared in the Hebrew Bible. According to Princeton professor of early Christianity history Elaine Pagels in her book The Origin of Satan, originally ha-satan was a messenger or an angel. He was not necessarily evil and was certainly not opposed to God. Ha-satan appears in the book of Numbers and in Job as an obedient servant of God. Ha-satan was also considered a heavenly prosecutor subordinate to Yahweh. He was aligned with Yahweh as his prosecutor. He opposed or obstructed activities of people or groups who were not acting according to Yahweh’s wishes or laws. Ha-satan made it difficult for people or groups to go against Yahweh. The root of his name, s’tn, means one who opposes, obstructs, or acts as an adversary. This meaning aligns with his role as a prosecutor for Yahweh. There is a similar meaning for diabolos, a Greek term which literally means “one who throws something across one’s path.” This was later translated as “devil,” and the term became popular among Christians as synonymous with Satan. In the roughly 400 years before the time of John the Baptist in early 1st century CE, ha-satan developed into Satan, an evil entity in dualistic opposition to Yahweh.

In the Hebrew Bible, a vision of cosmic struggle between the forces of good and evil was derived from apocalyptic sources that predicted supernatural cataclysmic events to occur at the end of the world. This vision was later developed by sectarian groups like the Essenes, a first-century Jewish sect that became followers of Jesus. The Essenes cleaved tightly to their perception of Satan as the source of evil in the world. They saw themselves as allied with angels—the forces of good—against Satan and his forces of evil. According to Pagels, the Essenes were austere and secretive and practiced strict celibacy, “…probably because they chose to live according to the biblical rules for holy war, which prohibit sexual intercourse during wartime. But the war in which they saw themselves engaged was God’s war against the power of evil—a cosmic war that they expected would result in God’s vindication of their fidelity.” (Note that all Pagels quotations in this chapter are from The Origin of Satan: How Christians Demonized Jews, Pagans, and Heretics.)

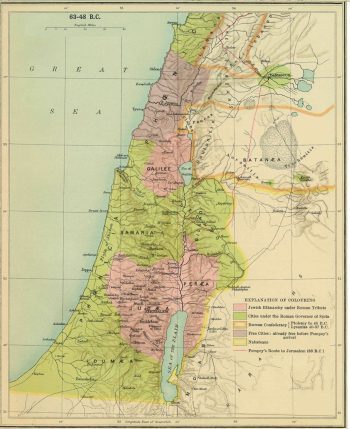

The Essenes saw the Roman occupation of Jerusalem—and the accommodation of the majority of Jews to that occupation—as evidence that the forces of evil had taken over the world in the form of Satan. Pagels explains that, according to the Essenes, Satan had, “infiltrated and taken over God’s own people, turning most of them into allies of the Evil One.” The Essenes referred to themselves as the “sons of light” and condemned the majority of Jews as the “sons of darkness.” Pagels states, “Had Satan not already existed in Jewish tradition, the Essenes would have invented him.”

Why an Evil Satan Became Necessary

When Yahweh was just one of many Hebrew deities, the concept of evil existing in the world was not a pressing issue. When something perceived as evil occurred, any of literally dozens of deities could be blamed. But when the Israelites were exiled to Babylonia in the 6th century BCE, Yahweh emerged as a monotheistic deity (for more information, see the The Origin of God chapter). Ha-satan evolved into an evil entity in opposition to the monotheistic Yahweh.

This view is articulated by Hellen Ellerbe, researcher and author of The Dark Side of Christian History:

The belief in one all-powerful God often elicits the question of why there is pain and evil in the world. Why does an almighty God, who creates everything, create human suffering? The most common answer is that there must be a conflicting force, power, or god creating the evil: there must be a devil. A dualistic theology arises which understands life to be a struggle between God and Satan, between good and evil, and between spirit and matter. The concept of a devil is exclusive to monotheism; evil is easier to understand and does not pose the need for a devil when there are many faces of God [as in polytheism, with its many deities].

Sir Keith Thomas, a Welsh historian, concurs in Religion and the Decline of Magic. He writes of early pre-monotheistic Judaism:

The early Hebrews had no reason to personify the principle of evil; they could attribute it to the influence of other rival deities. It was only the triumph of monotheism which made it necessary to explain why there should be evil in the world if God was good. The devil thus helped to sustain the notion of an all-perfect deity.

Leading scholar and author Rabbi Abner Weiss, Ph.D., writing about Judaism’s perception of Satan in relation to the monotheistic Yahweh, states:

The ancient world struggled with the coexistence of good and evil. They hypothesized a kind of demonic, divine force that was responsible for evil, arising out of the notion that a good god could not be responsible for bad things. [Judaism] found the notion of God having to share authority as limiting the omnipotence and even the omniscience of God. And therefore, Satan was never personified as a source of evil that was equally powerful. (See Where did Satan come from?.)

Satan’s Place in Christianity

Christianity’s perception of Satan diverged from Judaism’s perception. The supernatural drama between God and Satan and Jesus and Satan is told throughout the New Testament. New Testament stories of Satan and the devil are far too numerous to describe here, and the evolution of Satan in the history of Christianity is too complex to discuss here. However, I will touch upon a few facts that are of particular interest. According to Father Jose Fortea in Interview with an Exorcist, Satan appears thirty-five times in the New Testament, while appearing only twenty-one times in the Old Testament (which is much longer). Satan became a prominent figure in the imagination of Christians, and by around the 15th and 16th centuries, images of Satan began to appear in Christian art.

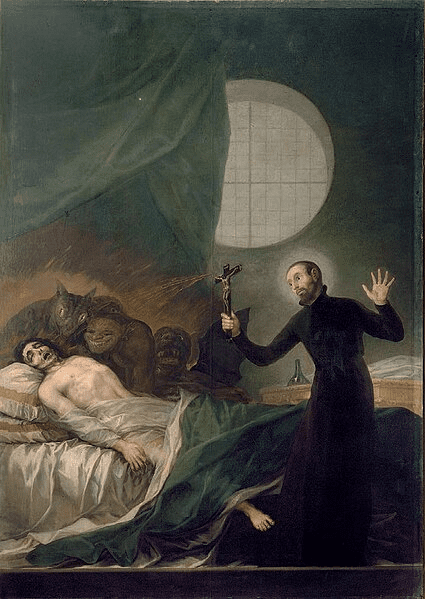

According to Christian tradition, Satan is an entity that seduces humans into sin. Most early Christians believed that Satan and his demons could possess humans, and a belief in demonic possession continues to this day. Satan is very real in the lives of many Americans. In 2021, the Pew Research Center conducted a survey about Americans’ view of suffering in the world. Forty-four percent of all U.S. adults said the notion that “Satan is responsible for most of the suffering in the world” reflects their views either “somewhat well” or “very well.”

The religious or spiritual practice of evicting demons from people or places is called exorcism. There are no statistics on the frequency of exorcisms in the U.S., but anecdotal evidence suggests that exorcisms have increased during the SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19) pandemic. For example, the Catholic Church in the U.S. has increased its level of exorcism services (per the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops: Exorcism.)

Christianity Embraces Satan as “Other”

In Christianity, Satan is generally seen as an angel who fell from grace and rebelled against God. Satan almost always represents “the other.” Christians have sometimes projected Satan’s personification of evil and opposition to God onto people whose religious and/or socio-cultural values and norms differ from their own—that is, onto “others.”

The cultural and social practice of defining certain people as “others” in relation to one’s own group, as in “we” versus “they” and in “us” versus “them,” may be as old as humanity itself. What may be new to western Christianity is how using Satan to represent one’s enemies casts a specific religious and moral condemnation upon the other. “We” become “God’s people,” and “they” become “God’s enemies.” Christians, having identified themselves with God and Jesus for some two thousand years, have identified their traditional opponents—Jews, heretics, pagans, and presumed witches—with Satan and the forces of evil.

Certainly, many Christians, although believing that they stood on God’s side, have refused to demonize their opponents. However, according to Pagels:

To this day, many Christians—Roman Catholic, Protestant, Evangelical, and Orthodox—invoke the figure of Satan against “pagans” (among whom they may include those involved with non-Christian religions throughout the world) and against “heretics” (that is, other Christians with whom they disagree), as well as against atheists and unbelievers…. For the most part, however, Christians have taught—and acted upon—the belief that their enemies are evil and beyond redemption.

Recent conspicuous examples of “us” as representations of what is good and “them” as representations of evil can be found in the political arena. In the mid-eighties, U.S. President Ronald Regan, a Christian, called the U.S.S.R “the evil empire,” and in 2002, U.S. President George W. Bush, also a Christian, referred to Iraq, Iran, and North Korea as an “axis of evil.”

Scapegoating Non-Christians

The Roman Catholic Church originally designated outside groups as “others” and their demonization through the ages is a classic case of scapegoating. Many protestant churches followed suit. “Scapegoating” is the process of singling out a group (or a person) for unmerited blame and adversarial treatment. Scapegoating dehumanizes others; one group (the “inner group”) identifies an outside group or individual as being different, making it the focus of the inner group’s fears, anger, or aggression. If a scapegoated group is stigmatized for being different or is perceived as evil, the scapegoaters will tend to avoid, bully, or persecute the members of that group. During its long history, the Catholic Church has scapegoated Jews, heretics, pagans, presumed witches, and other groups as being agents of Satan or possessed by the devil, thereby arbitrarily marking them as evil.

The Church has manipulated its followers into scapegoating others by employing this “us and them” (“in-group and out-group”) tendency. This tendency capitalizes on the basic human biological need to belong to a group for survival. In the case of the Church, scapegoating tends to bring the Church members closer together to unite against a perceived threat, and possibly keeps them from leaving.

Martin Lindstrom in his New York Times bestseller Buyology: Truth and Lies about Why We Buy addresses the uniting force of scapegoating:

Successful religions also strive to exert power over their enemies. Religious conflicts have existed since the beginning of time, and it doesn’t take more than a glance at the news to see that taking sides against the Other is a potent uniting force. Having an identifiable enemy gives us the chance not only to articulate and showcase our faith, but also to unite ourselves with our fellow believers.

The Church labeled their scapegoats as inferior and as threats, sometimes validating extreme mistreatment of them. As an example, the Church’s strategy of persecuting heretics in the Middle Ages was barbarous. People who simply had different religious beliefs were labeled heretics and given the option of converting to the Church or being executed. For more information, see the section on Thomas Aquinas in the Kingpins of Christianity chapter.

Why did the Catholic Church designate these groups as being evil? Their only apparent difference was that their beliefs didn’t conform to Church dogma; they simply had different beliefs. How is this evil? Did the church leaders view them as a threat, thinking perhaps that potential converts to Catholicism would join these groups instead?

Demonization of Jews, Pagans, Heretics and Witches

The characterization of Jews, heretics, pagans, and witches as “others” has often led to their persecution by Christians. In this section, I look briefly at each of these instances of scapegoating.Jews

In direct opposition to Christianity, Judaism rejected the view that Jesus was the Messiah. This opposition created a fundamental division between Christians and Jews. Although Jesus was a Jewish rabbi, his teachings and followers were not a part of the religious establishment in Jerusalem. Jesus’ growing influence posed a threat to both the Roman Empire and the Jewish religious power structure. It is apparent from the gospels that Jews played a role in his execution. However, there is extra-biblical evidence that Pontius Pilate ordered the crucifixion of Jesus for sedition (for more information, see the Discover Jesus Without Dogma chapter).

According to Pagels, “the New Testament gospels almost never identify Satan with the Romans, but they consistently associate him with Jesus’ Jewish enemies, primarily Judas Escariot and the chief priests and scribes.” This is despite the fact that it was the Romans who actually executed Jesus. The term Jewish Deicide describes the belief that the Jews as a people will always be held as collectively responsible for killing Jesus, even for successive generations of Jews. Biblical justification for Jewish Deicide is found in Matthew 27:24-25, wherein Pontius Pilate the Roman official who presided over Jesus’ trial claims to be “innocent of this man’s blood,” and the people (Jews) in the crowd answer, “His blood be on us and on our children!” In John 8:44, Jesus replies to the Jews, “You are from your father the devil, and you choose to do your father’s desires. He was a murderer …for he is a liar and the father of lies.” These two passages helped establish the conditions for Jewish Deicide.

As discussed in the “New Testament” chapter, biblical scholars estimate that the Gospel of Matthew was written approximately 50 to 60 years after Jesus died, and the Gospel of John, was written approximately 60 to 80 years after his death. These authors could not have possibly known Pontius Pilate or Jesus and certainly could not have known what they said. It seems apparent to us that these biblical passages are fictions that reflect the animosity of these authors toward the Jews. By inserting these and other such biblical passages into their gospels, these authors fueled Christians’ resentment toward Jews.

As a consequence of Jewish Deicide, Christians have often held the Jews responsible for the death of Jesus. This established the foundation for two millennia of systematic scapegoating of the Jewish people. For example, this led to draconian restrictions of Jews under the laws of many Christian nations and extremes of violence being perpetrated by Christians upon Jews. Scapegoating Jews continue, but it has become less widespread thanks in part to the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), which absolved the Jews, refuting the dogma of Jewish Deicide. This absolution has had a beneficial effect in the United States. A 2004 Pew Research report showed that 60% of Americans said that Jews were not responsible for the death of Christ versus 26% who believed the Jews were responsible.

Pagans

The religious connotation of paganism as we understand it today was created by the early Christian Church. Like “Satan,” the word “pagan” originally meant something very different. The Latin word paganus originally meant “rural” or “rustic” and was devoid of religious meaning. However, in the mid-4th century, a pagan was redefined by the Church as a person who worships many gods or goddesses, the Earth, or nature; such religious practices were then labeled paganism. Given that one way Christians have defined themselves has been by labeling groups that held opposing views as “others,” the term pagan was normally used in a derogatory sense. This has resulted in scapegoating of people identified as pagan. A synonym of pagan, heathen, is often found in Christian texts.

Among historians, there is consensus that Christians were a small minority in the Roman Empire in 300. Nevertheless, beginning soon after Constantine’s Edict of Milan legalized Christianity in 313, with the exception of a brief period, non-Christians were subject to discriminatory and hostile imperial laws. Pagan temples were destroyed and temple treasures were confiscated. Temples were converted to churches. By the time of the last anti-pagan laws, in the early 600s, non-Christians were a minority.

Note: It is important to understand that traditionally, the identification of a person or group as pagan has been an externally imposed label. Until the 20th century, individuals didn’t call themselves pagans to describe their religion.

Heretics

The word “heresy” originally meant “choice” or “thing chosen;” thus, a heretic was one who makes a choice. But the word “heretic” was redefined by early Church theologians to mean someone who teaches or believes something that goes against Church dogma. Today, the meaning of heretic has been broadened to include anyone who goes against official or accepted beliefs, especially the accepted beliefs of a church or religion.

An early Greek bishop, Irenaeus (ca. 130–ca. 202), was widely known in the development of Christian theology for defining orthodoxy and fighting heresy. The Catholic Church now recognizes him as a saint, and Pope Francis declared him the 37th Doctor of the Church in 2022. He is well known as the author of Against Heresies, written to refute the teachings of various Gnostic groups. In it he wrote, “One should not seek among others the truth that can be easily gotten from the Church [italics added for emphasis].”

Irenaeus continued:

Let those persons, therefore, who blaspheme the creator, either by openly expressed disagreement…or by distorting meaning [of the scriptures], like the Valentinians and all the falsely called gnostics, be recognized as agents of Satan by all those who worship God. Through their agency Satan even now, and not earlier, has been seen to speak against God…the same God who has prepared eternal fire for every kind of apostasy.

Unlike the pagans, whose losses were limited to their temples and the treasures they contained, heretics lost their lives. Perhaps the most famous person executed as a heretic was Joan of Arc (1412–1431), whose execution was arranged by Pierre Cauchon, Catholic Bishop of Beauvais, France. She was burned at the stake at nineteen years of age. The Church later realized that it had made a mistake and declared her a martyr and much later, in 1920, declared her a saint. However, such post-mortem absolution has not been granted for most of the people who were tortured and/or executed as heretics.

In the 16th century, an equivalent condemnation was decreed against Catholics, among others, when Martin Luther (1483–1546), founder of Protestant Christianity, expanded the traditional list of “others.” According to Pagels, “He denounced as ‘agents of Satan’ all Christians who remained loyal to the Roman Catholic Church, …all who challenged the power of the landowning aristocrats by participating in the Peasants’ War, and all ‘protestant’ Christians who were not Lutheran.” In January of 1521, the Catholic Church branded Luther a heretic.

Witches

I have added “witches” to Elaine Pagels’ list of Jews, pagans, and heretics. Like the words “Satan,” “pagan,” and “heretic,” the word “witch” originally meant something different than the Christian meaning in the Late Middle Ages and its meaning today. The original Hebrew word in Exodus 22:18 was mekhashepha. According to an article in the longest running Israeli newspaper Haaretz, “…what the original word meant when Exodus was written thousands of years ago, we cannot know, leaving us with only modern interpretations” (Thou Shalt Not Suffer a Witch to Live: A Murderous Mistranslation?). In researching the word mekhashepha, the authors conclude, “…we cannot know if the authors of Exodus meant poisoners, herbalists, or people who used magic for evil.”

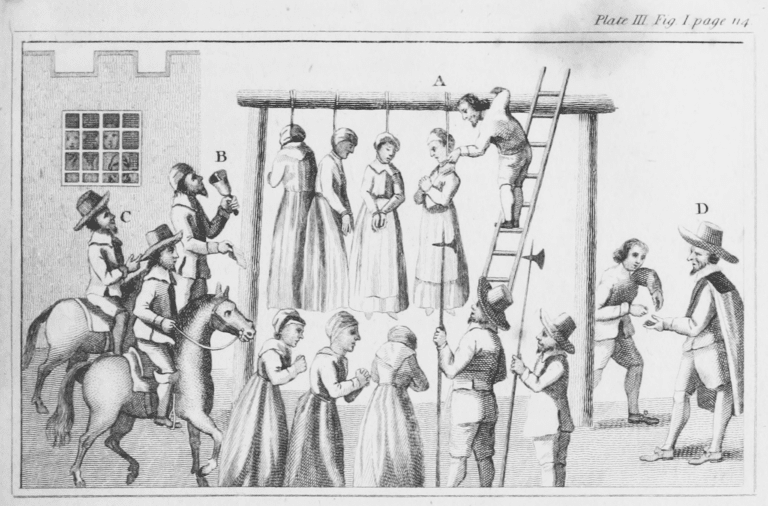

In the biblical translation sponsored by King James of Scotland (the King James Bible), mekhashepha was initially translated as “poisoner.” But the king arbitrarily changed “poisoner” to “witch,” amending Exodus 22:18 to read, “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live [italics added for emphasis].” This mistranslated biblical decree was soon used to justify horrifying human-rights violations and to drive the epidemic of witchcraft accusations and persecution across the globe to this day.

Like the Jews, pagans, and heretics, the people who were identified as witches were unjustly persecuted. This persecution was fueled by the misconception that the accused were agents of Satan. Scott Eaton, author of John Stearne’s Confirmation and Discovery of Witchcraft verifies that the inquisitors who accused people of being witches believed that witches were associated with Satan or the devil:

In many witchcraft narratives and confessions, the Devil played a major role as he was believed to form a pact with witches, giving them powers in return for their soul. At the witches’ sabbath, the Devil was purported to be the figurehead, where witches allegedly gathered to have sex with and to worship him. The intrinsic connection between belief in the Devil, heresy, magic and witches led to the construction of the diabolic witch.

Women were the main scapegoats and victims of this persecution. Of the witches that were burned at the stake or hung during the European wars of religion, most estimates are that 80% were women, mostly over the age of 40. Anne Llewellyn Barstow author of Witchcraze: A New History of the European Witch Hunts estimates that actually 85% of the witches burned at the stake or hung were female, and Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English in Witches, Midwives & Nurses affirm the 85% estimate.

Most were older women who healed with herbs and acted as midwives. The number of witches executed far exceeded that of the heretics. Michael D. Bailey, professor of history and author of Magic and Superstition in Europe, writes “Ordinary people – the kind who eventually got accused of being witches – didn’t perform elaborate rites from books. They gathered herbs, brewed potions, maybe said a short spell, as they had for generations. …Such practices were important in a world with only rudimentary forms of medical care.” Bailey continues,” From the 1400s through the 1700s, authorities in Western Europe executed around 50,000 people, mostly women, for witchcraft.” Anne Llewellyn Barstow pegs the number of people executed at 100,000.

None of this persecution and the resulting suffering was justifiable. According to authors of the Haaretz article quoted above:

Even without a definitive translation, it is unlikely that the King James Bible quote, “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live” is a wholly accurate translation. This means that the witch-hunts that Europe suffered were based on superstitious nonsense with no basis in the Bible or in reality.” [italics added for emphasis]

The Harmful Effects of Scapegoating

Scapegoating harms its victims and can also harm its perpetrators. In addition to causing egregious harm, such as torture and murder, defining a person or group as evil and scapegoating them may cause them significant psychological harm. They are likely to feel hatred, animosity, or resentment from others. Scapegoats may believe that they deserve this treatment and experience feelings of shame, guilt, and self-blame.

Since Satan is condemned as the enemy of God and Jesus and since Christians identify with God and Jesus, Christians naturally align with the Church against any group that the Church has scapegoated as evil. Thus, many Christians may imagine that they are fearing and hating on behalf of something noble and holy. They may imagine that they are taking the high ground and are being good and wise by attacking innocent people whom they have been taught to despise.

The inception and perpetuation of scapegoating is absolutely counter to the teachings of Jesus. Christians who are drawn into scapegoating may themselves be damaged by their inhumanity towards the scapegoats. Scapegoating causes resentment and other emotions like anger, contempt and hatred in the perpetrators, and harboring such emotions is psychologically damaging. It has been said that resentment is like drinking poison and then hoping it will kill your enemies. Resentment also damages us physically, interfering with our hormonal systems. These emotions affect our immune systems, making us more susceptible to disease and illness. Additionally, resentment and related harmful emotions can affect friendships and relationships with family.

Healing from Scapegoating Others

If you suspect that you have fallen into the habit of scapegoating anyone, here are some steps you can take to heal from the effects of scapegoating others:

- The first step is to recognize that you are scapegoating them. Many people who scapegoat don’t realize that this is what they are actually doing.

- Next, it is important to recognize the source or cause of your scapegoating. Were you taught this from your church? If so, does your church want you to believe that the group that is being scapegoated is evil, that it is associated with Satan or the devil?

- Consider that Satan and the devil are false concepts. When you realize that these are false concepts perpetrated by the Church, you can release the resentment or contempt toward these so-called “evil” groups.

- Lastly, it is important to understand that all people are equal in the eyes of God, even if we aren’t in the eyes of a particular church. I encourage you to reflect on Jesus’ teaching, “Love your neighbor as yourself.”

Love Your Enemies

Christians love Jesus. They also profess that they love God. A 2014 Pew Research Center report indicates three-quarters of Christians in the U.S. believe the Bible is the word of God. And the Bible explicitly instructs them to love their enemies.

Ideally, every Christian embraces love. In Matthew 5:43-44, Jesus tells his disciples, “You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, ‘Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.’ [italics added for emphasis]” As mentioned above, the author of the Gospel of Matthew had no way of knowing Jesus’ exact words; nevertheless, this passage aligns with Jesus’ teaching of love and forgiveness.

We Are All Equal

Scapegoating other human beings is counter to the fundamental truth that all human beings are equal, that we are one essence—love. Biblical scholars universally agree that Apostle Paul wrote Galatians 3:28, “There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus.”

Though Paul presumably wrote this specifically for his community of Christians, his fundamental message applies universally. We are all one—irrespective of whether we adhere to Christianity, some other religion, or no religion. Religious affiliations and beliefs do not change our fundamental equality.

In Conclusion

The meanings of the original words that were later translated as Satan and the devil by the early Christian church were misrepresentations of their original meanings, which were changed to connote evil. The Jews, pagans, heretics and witches that were labeled as evil were individuals who simply had different beliefs than their persecutors. They were innocent people who were persecuted and killed for their beliefs.

It seems obvious that the Roman Catholic Church changed the meaning of these words to manipulate its followers into turning against the groups these words were meant to portray. It would appear that the Church’s strategy accomplished a number of objectives. Killing members of these groups prevented them from sharing their beliefs with the Church’s congregation. By branding these groups as evil, the congregation would be reluctant to interact with them and share ideas, thereby helping to ensure that Church members would remain faithful Christians. The Church’s followers became unwitting co-conspirators in scapegoating.