Chapter 9.

Original Sin

This chapter explores the Christian concept of original sin, both in its original meaning and as it was revised and promulgated by Bishop Augustine of Hippo (354-430). The sections are as follows:

Note: CE stands for Common Era, which began with the birth of Jesus. The biblical scripture is from the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV).

The story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden is well-known among Christians and Jews. The story comes from the Hebrew Bible, which is the source of the Old Testament in the Christian Bible: “And the Lord God commanded the man, ‘You may freely eat of every tree in the garden; but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall die.’” (Genesis 2: 16-17). As the story goes, God next created Eve, who was persuaded by a serpent to eat fruit from this tree. She then gave some of the fruit to Adam, who also ate it. This constituted an act of disobedience to God.

Today, biblical scholars unanimously agree that the Adam and Eve story was a myth created by the ancient Hebrews. The story of Adam and Eve was created by members of Hebrew tribes over 2,500 years ago. This act of disobedience was considered a sin by the Hebrews. The word “sin” is a translation from the Hebrew word, cheit, meaning “missing the mark,” a word originally associated with archery. For more information, see the Hebrew Bible chapter.

Early Christians interpreted the story of Adam and Eve as about moral freedom and moral responsibility. For the nearly four centuries before Augustine, most Christians, like their Jewish predecessors, would have believed that Adam’s sin brought suffering and death upon humanity. Nevertheless, it was also widely believed that God gave mankind the gift of free will, liberty, autonomy, and self-governance, just as Adam had been given the ability to freely choose between good and evil. Yet, hundreds of years after the birth of Jesus, this original interpretation of Adam’s disobedience by the Hebrews was to become mostly superseded by Augustine’s interpretation.

Enter Augustine, Bishop of Hippo

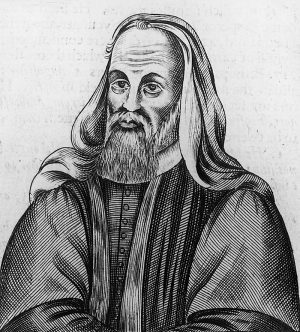

Bishop Augustine of Hippo (354-430) is credited with inventing the concept of original sin in the form that became the teaching of the Roman Catholic Church. His teachings would eventually transform teachings on freedom, on sin and redemption, and on sexuality for Roman Catholic Christianity and future western Christian denominations. For more information about Augustine, see the Kingpins of Christianity chapter).

Augustine was a prolific writer, who wrote in Latin. Among his most important texts is Confessions, which consisted of 13 books. Many of Augustine’s ideas presented here are in the form of quotations taken from his various texts, many of which are cited in this chapter.

Roman emperor Theodosius I (347–395) made Roman Catholic Christianity the official religion of the empire in 381. Not long after this event, Augustine contrived his version of original sin. Original sin had first been alluded to over two hundred years earlier by Irenaeus, Bishop of Lyon (130–202). But, his writings on original sin were somewhat optimistic, had nothing to do with sex, and contrasted sharply with the subsequent writings of Augustine.

St. Paul and his epistles were a major influence on Augustine. So much so that even though he lived centuries before Augustine, St. Paul is considered Augustine’s mentor. Their combined impact on Christianity is immensurable. Sadly, both believed that Adam and Eve were real people.

Augustine’s Guilt and Shame from His Lust and Fornication

Augustine’s interpretation of original sin reflected his own sexual desires. Starting in his adolescence, he was consumed by those desires, which he readily acted upon until his conversion to Christianity in his early forties.

Augustine reflects, “in the sixteenth year of the age of my flesh … the madness of raging lust exercised its supreme dominion over my sexual desire, my invisible enemy trod me down and seduced me.” Of his sexual involvements he admits, “I drew my shackles along with me, terrified to have them knocked off.” Acknowledging that his friend was “amazed at my enslavement,” Augustine reflects that “what made me a slave to it was the habit of satisfying an insatiable lust” (Confessions). Augustine referred to these sexual desires as “concupiscence” (hurtful desire; sinful lust). It is by concupiscence, wrote Augustine, that original sin is transmitted to Adam’s descendants, enfeebling freedom of the will without destroying it.

Augustine had become celibate by the time he became a Catholic priest at age 44. Still, he believed that we are helpless to control sexual desire, that “this diabolical excitement of the genitals” arises in everyone, hideously out of control. Even in marriage he finds “boundless sloughs of lust and damnable craving.” If not for the restraints imposed by Christian marriage, “people would have intercourse indiscriminately, like dogs.”

Augustine believed that sexual desire naturally involves shame:

“A man by his very nature is ashamed of sexual desire.” …“Lust is an usurper, defying the power of the will, and tyrannizing the human sexual organs.” … “like water I boiled over, heated by my fornications.” (Confessions)

“Nothing is so powerful in drawing the spirit of a man downwards as the caresses of a woman and that physical intercourse which is part of marriage.” (Soliloquies)

Loss of Free Will

There are indications that Augustine accepted the existence of free will in the 380s CE, though he held that free will was weakened, though not destroyed, by original sin. However, sometime after 412 CE, his position changed to a loss of free will except in the choice to sin.

According to Augustine, Adam’s desire to master his will became his downfall. Adam had received freedom as his birthright, but in Augustine’s perception, the first man “conceived a desire for freedom.” It was this desire that was the root of sin: “The fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil is personal control of one’s own will.” It was Adam’s desire for self-governance that led Augustine to write, “The soul, then, delighting in its own freedom to do wickedness, and scorning to serve God …willfully deserted its higher master.” Adam’s desire for autonomy led him into a “life of cruel and wretched slavery instead of the freedom for which he conceived a desire.” (The City of God against the Pagans)

Augustine combined the question of self-governance with rational control over sexual impulses. He came to believe that his own will was divided, and as a result, he was powerless: “Myself I willed it, and myself I nilled it: it was I myself. I neither willed entirely, nor nilled entirely. Therefore I was in conflict with myself, and …was distracted by my own self.” (Confessions)

Augustine interpreted the Adam and Eve story as one of human bondage. In attempting to explain his own inner conflicts, which were an integral part of his existence, Augustine insisted that since he suffered much of this “against my own will, …I was not, therefore, the cause of it, but the ‘sin that dwells in me’: from the punishment of that more voluntary sin, because I was a son of Adam.” (Confessions)

Inherited Guilt Transmitted through Conception

Augustine taught the concept of “inherited guilt”—that we all sinned “in Adam.” Obviously, Augustine could not have known about evolution at that time, so he didn’t know that the Adam and Eve story is a myth. However, this lack of knowledge does not excuse his interpretation of that myth. He declared that the whole human race inherited from Adam a nature irreversibly damaged and corrupted by sin.

His sexualized interpretation of sin and his revulsion from “the flesh” is based on his own peculiar belief that we contract the disease of sin through the process of conception. Augustine saw the sin of Adam and Eve as inseparable from the sexual act: sin is passed on through sexual intercourse. He taught that humanity is tainted with sin “from the mother’s womb.” He wrote, “We did not have individually created and apportioned forms (bodies) in which to live as individuals.” What existed already was the “nature of the semen from which we were to be propagated.” Augustine wrote that it is the semen itself, already “shackled by the bond of death,” that transmits the damage incurred by sin. Hence, Augustine concluded that every human being ever conceived through semen is already born contaminated with sin. Augustine failed to consider how a just and loving God could blame humanity for something done by a distant ancestor (much less a fictional character).

He intended to prove that every human being, with only one exception, is in bondage not only from birth but indeed from the moment of conception. The one exception, according to Augustine, was Jesus, who was conceived without semen, based on the doctrine of the virgin birth.

Mistranslation of Romans 5:12

Augustine was considered a brilliant theologian and orator, but as a biblical scholar he was severely handicapped. The original biblical texts were in Hebrew and Greek, but Augustine couldn’t read Hebrew and had very little Greek (there is no evidence that he ever saw any original Greek version of the gospels). Therefore, he had to rely on Latin versions, which being handwritten by scribes, were not always reliable translations.

Augustine was notoriously misled by a Latin rendering in Paul’s letter to Romans 5:12. The Greek original reads, “Death spread to all men, through one man, in that [i.e. because] all men sinned. [italics added for emphasis]” In contrast, the erroneous Latin translation reads, “death spread to all men, through one man, in whom all men sinned. [italics added for emphasis]” Based on the Latin mistranslation of this passage, Augustine interpreted the last phrase as referring to Adam. He thought that Romans 5:12 meant that the sin of that “one man,” Adam, brought universal death and sin upon humanity. Augustine denied that human beings have free moral choice. He insisted that the nature of the whole human race had been irreversibly damaged by a sin universally inherited from Adam: “For we were all in that one man, since all of us were that one man, who fell into sin through the woman who was made from him.” (De Civitate Dei)

Departure from Traditional Christian Doctrine

Augustine’s theory of “original sin” and weakened free will was a radical departure from existing Christian doctrine. His idiosyncratic and pessimistic view contradicted the teachings of the earlier revered Church fathers. The traditional Christian (and Jewish) belief regarded moral choice as the birthright of humanity, who is “made in God’s image.” Many traditional Christians believed that Augustine’s theory contradicted the very foundation of the Christian faith: the goodness of God’s creation and the freedom of the human will. They believed that even if before baptism we are stained by sin, baptism cleanses the believer of all sin.

Augustine insisted that we became susceptible to death solely through an act of will, “Death comes to us by will, not by necessity.” That is, to Augustine, death exists solely because of Adam’s choice to sin, a sin that was inherited by all of humanity. This interpretation contradicted traditional beliefs. For example, consider one contemporary, John Chrysostom, archbishop of Constantinople. Like most Christians of that time, Chrysostom took Romans 5:12 to mean that Adam’s sin brought death into the world, and death came upon all only because all sinned. Chrysostom was among the foremost theologians of Augustine’s contemporaries and is second only to Augustine in the quantity of his surviving writings. He was a controversial figure among the powerful elite. For example, according to the Encyclopedia Britanica, Chrysostom “believed that personal property is not strictly private but a trust. In his eloquent, moving, and repeated insistence on almsgiving, he frequently taught that what was superfluous to one’s reasonable needs ought to be given away.” Eventually, he was exiled for his beliefs.

Augustine’s theology was met with resistance by the leading theologians of his time. The first opponent who denied Augustine’s idea about death was Pelagius, a prominent theologian who advocated free will. Pelagius argued that universal mortality cannot be the result of Adam’s punishment, for God, being just, would not have punished anyone but Adam for what Adam alone had done. Moreover, mortality was part of nature, something that humans share with every other species, and death was never within the power of any human to choose or reject.

Another theologian, Julian, bishop of Eclanum, a distinguished leader of the followers of Pelagius, was very vocal in challenging Augustine on his theory of original sin. He accused Augustine of inventing original sin. Among the many views of Augustine that Julian contested was the assertion that through an act of will, Adam changed the structure of the universe itself, permanently corrupting human nature and Nature itself.

For more than 12 years, Augustine and Julian debated their respective views, without resolution, until Augustine died. However, in his declining years, Augustine admitted that he was unable to fathom the Christian teaching on free will. Thereafter, Julian was deposed and excommunicated by the Roman Catholic Church because he refused to sign Pope Zosimus’ edict against Pelagius.

Despite such active resistance, Augustine succeeded in persuading many Bishops and several Christian emperors to silence critics by having them declared “heretics”. People who still embraced earlier traditions of Christian freedom were condemned. Among them was Pelagius, who was declared a heretic by the Council of Ephesus in 431 CE. Julian charged that Pelagius’s opponents used personal influence at court, bribery, and false accusations.

Condemnation of Sex (Even in Marriage)

Augustine’s experience of sex had consisted of illicit love affairs from which he gained a sense of misery and guilt. He could never quite disguise his loathing and distrust of sex. In later life, he equated all sex, even in marriage, with wickedness and sin.

Augustine wrote a treatise in 401 CE, On the Good of Marriage, which has left a lasting black mark on the entire Christian tradition.

In On the Good of Marriage, Augustine preached, “Husbands, love your wives, but love them chastely. Insist on the work of the flesh only in such measure as is necessary for the procreation of children. Since you cannot beget children in any other way, you must descend to it against your will, for it is the punishment of Adam.”

Augustine’s conviction that sexual appetite is evil by its very nature became the great tradition of the church. He held that sexual intercourse in marriage for the sake of children is good; but for any other reason, it is a sin. “There are men incontinent to such a degree that they do not spare their wives when pregnant.” Logically, it would follow that the pregnant wife should refuse her husband and not allow him to sin with her. However, Augustine argues to the contrary: she must admit her husband because he has dominion over her.

Augustine wrote, “Abstaining from all intercourse is certainly better than marital intercourse itself which takes place for the sake of having children.” It would follow then that the ideal marriage would be made up of celibates. Also, sex during the safe period with the intention to avoid pregnancy is gravely sinful: “For intercourse that goes beyond the necessity to procreate no longer obeys reason but passion.”

Augustine’s profound pessimism about sex, marriage, and original sin found its supreme champion in Pope Gregory I (540–604). He was one of the first pontiffs to put his seal of approval on the works of Augustine. Pope Gregory agreed with Augustine that sexual desire is sinful in itself. He wrote to another Augustine, the apostle of England, “Sexual desire is absolutely impossible without fault.” Therefore, every act of sex, even in marriage, needs atonement. Gregory wrote, “We come into the world from corruption and along with corruption, and we carry corruption with us.” Married couples were warned not to have intercourse on their wedding night in case they desecrated the sacrament of matrimony. Gregory said that intercourse during pregnancy is sinful, like Augustine, but also during lactation as well. (Vicars of Christ by Peter DeRosa)

The Church’s rules on sex were not limited to activity between two people. In the Catechism of the Catholic Church 2352, “By masturbation is to be understood the deliberate stimulation of the genital organs in order to derive sexual pleasure. Both the Magisterium of the Church, in the course of a constant tradition, and the moral sense of the faithful have been in no doubt and have firmly maintained that masturbation is an intrinsically and gravely disordered action.” This ruling established masturbation as a mortal sin, and it continues to be considered a mortal sin to this day.

Eventually, there was neither pope, nor theologian who did not follow Bishop Augustine’s views on sex. Through them, Augustine has influenced lay people for generations. The view that sex is exclusively procreative became western Church orthodoxy and has remained so for well over a thousand years, into the present day. During this time the act of sex is described in terms of sin, never in terms of love.

In Conclusion: Augustine’s Legacy

Around the time that the Roman Catholic Church was established, it had begun a long-running conflict with independent intellectual pursuits. This conflict began with the Church opposing Pelagius, a monk and theologian whose theology emphasized the primacy of human effort in spiritual salvation. He taught that it was unjust to punish one person for the sins of another; therefore, infants are born blameless. As I have discussed, the Church also opposed Origen’s theories of reincarnation in favor of Augustine’s grim view of humanity.

According to Helen Ellerbe in her book The Dark Side of Christian History:

The tenets formulated in response to early heretics lent doctrinal validation to the Church’s control of the individual and society. By opposing Pelagius, the Church adopted Augustine’s idea that people are inherently evil, incapable of choice, and thus in need of strong authority. Human sexuality is seen as evidence of their sinful nature. By castigating Origen’s theories of reincarnation, the Church upheld its belief that a person has but one life in which to obey the Church or risk eternal damnation.

In contrast, Augustine’s theory on original sin was firmly rejected by eastern Christianity. The Orthodox Catholic Church, which is the second-largest Christian denomination, remains free of Augustinian influences. Likewise, Judaism does not have a concept of original sin as an interpretation of the Adam and Eve story.

Conversely, both Roman Catholics and Protestants usually regard the story of Adam and Eve as virtually synonymous with original sin. Augustine’s pessimistic views on sexuality, politics, and human nature have become the major influence on western Christianity. His theory on original sin has stained western culture, Christian or not, and continues to affect western civilization to the present day.